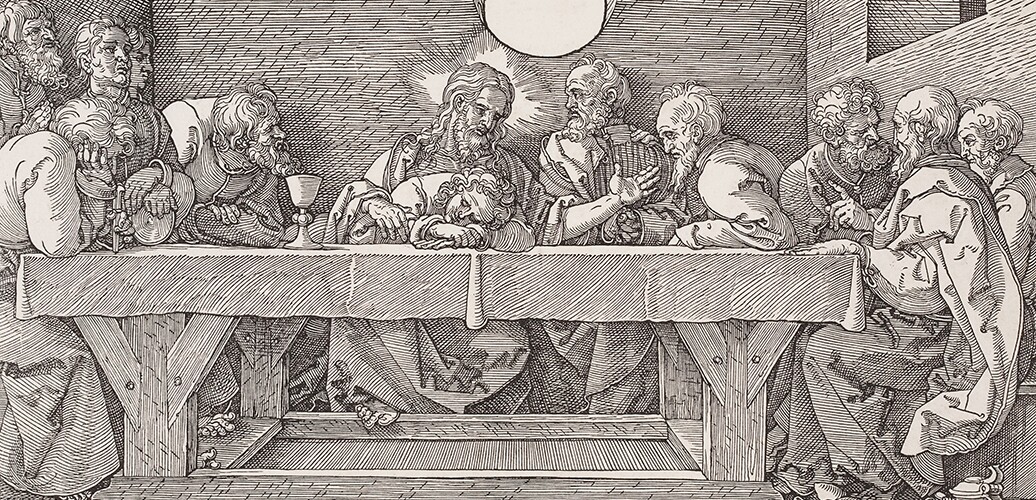

Bold lines and energetic shapes carve out this poignant Last Supper scene. Albrecht Dürer’s expressive use of robust and repeating black lines, compositional force and the visual vigor of the woodcut medium magnificently convey the power of this moment.

Dürer is celebrated for his inventive genius with the woodcut medium. He introduced a totally new way of expressing ideas and imagery through this artform. Original prints were the primary way that visual and written information was captured and shared during this period. They also offered an accessible, powerful means of religious devotion and education. Dürer’s technical brilliance and innovative compositions brought an unprecedented means of storytelling through art.

In his Last Supper scene, Dürer arranges a symphony of ordered and small diagonal lines to animate the scene. The sophisticated interplay of lines is complex yet perfectly restrained, giving an effect of austerity and monumentality to the image. The asymmetrical perspective that Dürer introduces for visual interest encourages viewers to look closely and signals this is not a typical Last Supper scene.

The moment Dürer depicted is unexpected. He does not represent Christ’s institution of the Eucharist, nor the indication of his impending betrayal. Instead, Jesus sits at the center of a table with 11 of his disciples after the announcement of his betrayal has occurred. Judas has left, and the other disciples are visibly distraught. Christ is marked by a triad halo, which in Christian art is historically reserved for Christ and God the Father. Jesus makes an oratorical gesture with his left arm, likely offering these words:

“I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.” (John 13:34-35)

Images and woodcuts such as this offered Christians of the Early Modern period a fresh source of inspiration and devotion. Different from large altarpieces, sculpture or stained glass windows in churches, this powerful image is literally on paper and thus could be held in one’s hands, or viewed in an album, bringing the Passion story close, allowing reflection and prayer. Sometimes, the text would accompany such images; other times, we can imagine that those who looked upon this image may have recited prayers or recalled scripture.

Today, we can continue this meaningful practice and be connected to all those who did so before us.

Joanna Reiling Lindell is vice president of Audience and Experiential Engagement at Thrivent and chief curator of the